To safeguard both our society and economy, we must fundamentally change the way we interact with the physical environment of the Earth. The interactions that matter most are those that happen in the place-based socio-technical systems that provide us with energy, mobility, food, housing, water, and other goods and services characteristic of modern human civilisation.

The change we need is not incremental. We must rewire almost all aspects of how societies operate: technologies, values and social norms, materials extraction and use, institutions, education and skills, economic paradigms, policy and regulation, and financial flows. The sustainability movement uses a technical term for such deep and irreversible change in economic, technological, societal, and behavioural domains: transformation.

In the context of climate change, transformative change is not just about depth and irreversibility but also about directionality. Human economic activity must transition from its extractive, exclusive, and unsustainable status quo to a regenerative, inclusive, and sustainable model that respects the natural boundaries of our planet and the social needs of our communities.

The logic—the collection of paradigms, structures, and practices—under which money is invested is a powerful driver of a system’s behaviour. What determines such a logic is the purpose for which money is deployed. If invested effectively, money can cause or accelerate the accomplishment of that purpose.

We thus define transformation capital as …

an investment logic intending to deploy capital to catalyse directional transformative change of socio-technical systems to build low-carbon, climate-resilient, just, and inclusive societies.

Put simply, transformation capital is a systemic investment approach for catalysing sustainability transitions in the real economy.

The Nature of the TransCap Approach

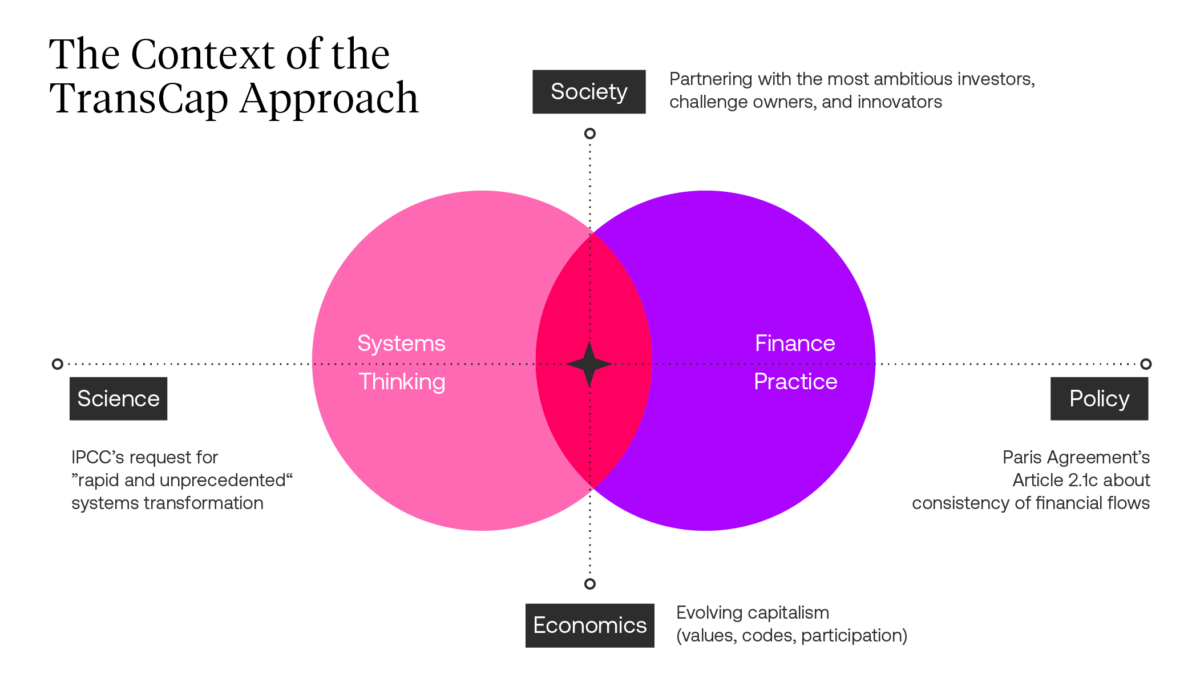

As a capital deployment logic, transformation capital inhabits the nexus of systems thinking and investment practice. It recognises that financial flows occur in networks of actors and relationships, which are bounded by institutions and social norms and constituted by people. It aims to build a bridge between the Paris Agreement’s goal of realigning financial flows and the IPCC’s call for transforming socio-technical systems.

The TransCap approach recognises that today’s conception of wealth is no longer an appropriate proxy for human prosperity. Nor is the current version of capitalism future-proof. This creates the need for investors to expand their notion of value to include non-financial goods such as social equality, political stability, intergenerational equity, and ecological sustainability, without which the traditional concept of wealth is threatened.

The World as a Complex Adaptive System

A hallmark of the axioms underpinning transformation capital is that the world operates as a complex adaptive system. Such systems consist of many parts that interact dynamically, process information, and adapt their behaviour.

Complex adaptive systems share three defining characteristics: they constantly evolve, they exhibit aggregate behaviour (emergence), and they anticipate. These characteristics endow complex adaptive systems with a set of peculiar features, such as self-organisation, feedback loops, tipping points, and non-linear growth. Importantly, these systems behave in non-deterministic ways, making it difficult to predict cause-and-effect relationships in advance.

The nature of complex adaptive systems has profound implications for designing intervention strategies, not least for how to deploy capital in service of system transformation. In complex adaptive systems, deterministic action plans are bound to fail, predictive tools are unhelpful, and excessive categorisation is constraining. More promising approaches emphasise exploration, experimentation, and rapid learning, and they try to harness the defining characteristics of complexity.

The Importance of Intent

At the heart of transformation capital sits intent. While the concept of intent is related to that of objectives, it lives on a higher level of abstraction and is more closely related to the idea of purpose. This distinction matters because many sustainable finance initiatives (SFIs) are explicit about their objectives but not about their intent.

In fact, many SFIs pursue laudable environmental and social objectives but operate with the intent of retaining a version of capitalism that ascribes a singular purpose to investment capital: to multiply itself. In contrast, transformation capital intends for investors to deploy capital primarily to create change dynamics that propel a system in a specific direction, both in order to set the system on an environmentally and socially sustainable footing as well as to enable the continued multiplication of capital in the long run.

Being clear about intent also matters because what investors set as their priorities determines what they care about. Investors pursuing systemic change will interrogate the universe of investable assets with different frameworks and metrics for evaluating potential, success, and failure. They will also bring a different spirit and mindset to their investment practice.

Setting Directionality through Missions

The directionality so characteristic of systemic investing is set by the challenge owner: a government, multilateral organisation, foundation, corporation, or individual with the resources, influence, sense of agency, and mandate to address climate change on behalf of others. It must be articulated in a transformation agenda—or “mission”—as a statement of intent.

When imagining the future, it is useful to keep in mind that systems move from one state to another through an evolutionary process. One of the marvels of evolution is that it produces a great variety of designs that are fit for a specific purpose. This means that there is a multitude of different system designs that meet a specific intent. So what counts for sustainability transformations is not to perform a precision landing on an individual design (i.e., to meet clearly defined objectives) but instead to arrive somewhere within a general landing zone, such as the “safe and just space for humanity” suggested by Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics.

However the landing zone is defined, it is useful to recognise that systems are path-dependent—where they come from determines where they can go next. Further, transformations do not occur as discrete phenomena but progress along a gradient, evolving forward along a series of "adjacent possibles". This means that systemic investors must develop a sense of the transition pathways that a socio-technical system could reasonably take given its current resource base and configuration.

Complex adaptive systems have self-organising properties. Investors can harness these by deploying capital in a way that changes a system’s dynamics. This requires that their impact assessments focus on indicators of transition dynamics rather than on static outputs such as project-level emissions savings.

The Role of Capital and Investors in Driving Systemic Change

How, exactly, capital drives a system’s behaviour is not well understood, particularly in the context of sustainability transitions. The TransCap Initiative will operate with two bold assumptions: that monetary flows can trigger systems-transformative dynamics, and that investors can be active agents of change and determine the shape and direction of these dynamics.

Irrespective of the agency of money and that of the people deploying it, it is clear that the causal chain between interventions in secondary markets (such as stock exchanges) and effects on emissions and resilience in place-based systems is long. This is why the transformation capital approach focuses on the real economy, working as close to the sources of emissions, resilience, justice, and inclusiveness as possible.

The Humanscape

Systems thinking is an abstract discipline, and so is finance. But even in the institutionalised world of finance, the system’s behaviour ultimately emerges from the actions of people. This is why transformation capital emphasises the agency of the individual, calling upon decision-makers to critically reflect upon the role they play in shaping the future, and to choose action over complacency and responsibility over deference.

Yet a strong sense of individual agency is not the only people-related success factor. Systemic investing is inherently collaborative. So actors from all parts of society—civil servants, sustainable development specialists, asset owners, finance professionals, regulators, trustees, auditors, and corporate executives—must work together in a trustful, respectful, and mission-oriented manner.

Impact Promise

Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement calls upon the world to “make financial flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.” What that means from a practical perspective remains largely unclear, and work focused on operationalising this article has only just begun. Nor is it obvious how today’s most prominent sustainable finance initiatives can build a bridge to the IPCC’s call for real-economy transformations at the scale and pace we need.

The TransCap approach is not a sure-fire recipe for driving the kind of deep, structural change the world now needs. But the intent, mindset, sense of agency, and method with which it goes about the challenge are reasons to believe that it holds the promise of increasing the effectiveness with which we deploy capital for transformative effects.